Limitations in current regulations, lack of reporting culture cause for dangerous goods-related incidents

Developing a work culture where individuals feel free to report incidents without the fear of punishments, avoiding blame and taking responsibility was at its core.

The recent incident of fire at HKIA initiated many discussions among the air cargo industry safety professionals. Developing a work culture where individuals feel free to report incidents without the fear of punishments, avoiding blame and taking responsibility was at its core.

As several airlines announced embargoes on Vivo and logistics companies involved in the fire at Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA), air cargo dangerous goods experts and consultants discussed the need for a temporary ban, no-blame culture, just culture and training across the industry.

Paul Horner, managing director, Dangerous Goods Safety Group UK, said, “Placing embargoes on logistics companies each time we have an incident is maybe a bit harsh. Aviation safety should operate a ‘no blame culture' where we treat incidents as an opportunity to improve.”

Henrik Ambak, senior vice president, cargo operations worldwide at Emirates, informed that just culture and temporary bans after incidents are completely unrelated matters.

“It is normal practice that when a serious incident occurs that you then try to neutralise any apparent root causes until you have the final investigation outcome,” he said.

“Just culture is a workplace culture where staff as part of the continuous improvement process are encouraged to report incidents, risk and failures (typically confidentially) without fear of punishment. Noting that punishment may always apply for actions criminal, reckless or with done the intent to cause harm and damage,” he added.

Also Read: Need for no blame culture as logistics firms, Vivo banned after HKIA fire

After the fire, Emirates suspended the transport of products from Vivo. “We did not suspend the agent as the shipment as per initial information appear correctly declared and documented. This is not a punishment of Vivo but buying time for the investigation to give us the understanding of the true causes,” Ambak said.

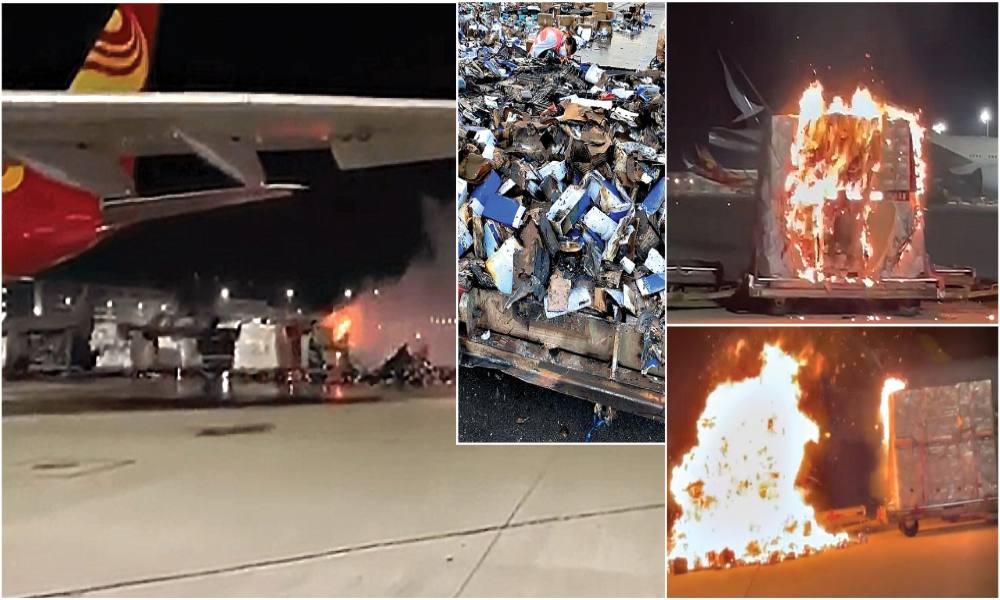

HKIA incident

On Sunday, April 11, 2021, one of the three air cargo pallets with Vivo Y20 smartphones and related accessories due to be shipped to Bangkok caught fire on the tarmac of HKIA before loading to an Airbus A330-200F aircraft of Hong Kong Air Cargo. The fire was later spread to the other two pallets as well.

Hong Kong Air Cargo immediately imposed an embargo on all shipments of Chinese smartphone manufacturer Vivo and the freight forwarders CargoLink Logistics HK and Sky Pacific Logistics HK. Carriers like SpiceJet, GoAir, Garuda, IAG Cargo, Cathay Pacific and Lufthansa Cargo also announced a ban on shipments of Vivo.

Hong Kong Civil Aviation Department (HK CAD) has commenced an investigation to identify the cause of the fire.

No penalty culture

“When people feel free to report we learn and grow, when they don’t, we face potential catastrophe,” as described by David Alexander, general manager of Johannesburg-based Professional Aviation Services and ICAO AVSEC PM: aviation security and training specialist.

“A ‘no penalty’ culture would be in force when any person in an organisation would feel free to report anything they had seen or done (for example dropped a pallet of cell phones) without fear of repercussion. If this is not part of an organisations culture people would tend to hide their own mistakes whenever possible for fear of consequence or would not report something for fear of repercussion,” he said.

Regarding the just or no penalty culture he thinks that the air cargo community need to make some very important distinctions.

“Very importantly we are talking about an honest mistake or accident not a willful act of disobedience, destruction, or corporate sabotage. We are not talking about creating a corporate culture where ‘anything goes'. We are striving to create a learning and development culture where continuous improvement is part of organisational DNA,” said Alexander.

He points that organisations should search for root cause and not blame. “Avoid blame, it is toxic,” as he says it.

“Sometimes the default (particularly in a very high-profile incident) is to seek somebody, anybody, to blame. And preferable somebody outside of your organisation! It was them, not us, we did nothing wrong,” he said.

Eric Gillett, dangerous goods inspector at Qatar Civil Aviation Authority, said, “In a blaming culture where individuals are fired, fined or otherwise punished for making mistakes they are often hidden preventing lessons to be learned. But a balance needs to be struck as reckless or negligent behaviour should not go unpunished.”

Potential reasons for fire

Kamlesh Taank, managing director of Nairobi-based Dangerous Goods Specialists, argued that the best practice is training, as this limits risks involved in the safe transport of dangerous goods.

He raised five questions if the whole pallet or pallets, that caught fire had mobile phones with lithium-ion batteries.

1. Were the lithium-ion batteries tested as per the UN manual of tests and criteria?

2. Were the lithium-ion batteries of poor quality or counterfeits?

3. Were they packed, marked, labelled and declared as per the ICAO technical Instruction and the IATA DG regulations?

4. Were the shippers/forwarders personnel trained in the safe handling of dangerous goods?

5. Were the ground handling agents aware, of the presence of lithium batteries, whilst building up the airline pallets or offloading the same from the trucks etc.?

Meanwhile, Gillett suggested three potential causes of fire.

1. Damage due to mishandling. e.g. if the packages were dropped or pierced by forklift. If there isn’t a just culture, it’s unlikely that mishandling will be discovered unless shown on CCTV.

2. An absence of UN38.3 tests for example if the phones are counterfeit (presumably Vivo are fully aware of this requirement).

3. A manufacturing fault not captured by QC (like the Samsung Galaxy issue). I suspect that is why the carrier placed a ban on Vivo pending the conclusion of the investigation.

“The goods were virtually destroyed by the fire so determining 2 or 3 above may not be possible. Another element discussed in the media is the time that elapsed without RFFS in attendance and speculation that ground staff took video without calling them,” he added.

Gillett pointed to the limitations of current regulations and the need for a reporting culture. “Within many states, including the UK, there are millions of shippers as the population has easy access to mail services. In addition, exposure to undeclared dangerous goods has increased following the advent of e-commerce whereby goods are sold and distributed by an increased number of small and medium enterprises.”

“Shippers are not typically required to hold any aviation approval; therefore, states cannot proactively identify all shippers, nor schedule oversight on all their dangerous goods activities. Instead, some states implement regulatory actions in response to occurrence reports received. This necessitates a strong reporting culture within a state as the report provides the necessary input prompting an investigation and response aimed at preventing recurrence,” he added.

Gillett informed that ICAO Annex 6 will soon require the air operator to conduct a specific safety risk assessment on the range of items placed within cargo compartments.

“This presents a significant challenge to air operators because shippers and forwarders are the customers of airlines, not their service providers. Further, as cargo is often consolidated, and consolidations may themselves be consolidated prior to being ultimately offered for air transport, it can be difficult for the air operator to apply effective controls at source,” he said.